Vickie Blackwell Morrow was born the fifth of eight children to a truck driver and homemaker in a small town in North Carolina during the peak of the Civil Rights Movement. She is a graduate of Elon College and Old Dominion University. While at Elon, she met her husband, David, who began a career in United States Air Force in 1984. For nearly thirty years they served on Air Force Bases around the world, where she volunteered and taught public school.

Vickie Blackwell Morrow was born the fifth of eight children to a truck driver and homemaker in a small town in North Carolina during the peak of the Civil Rights Movement. She is a graduate of Elon College and Old Dominion University. While at Elon, she met her husband, David, who began a career in United States Air Force in 1984. For nearly thirty years they served on Air Force Bases around the world, where she volunteered and taught public school.

She is the mother of two adult children and teaches courses at a local university.

Her nonfiction story “He Keeps on Truckin'” was awarded second place in our “On Courage” contest.

I write because: writing calms the anxiousness that often stirs my soul— the anxiousness that is stirred when I witness injustice and inequality. When life happens and my mind becomes fragmented, writing is the glue that holds it together.

Something surprising that I have learned about courage over the years is: most people who are truly courageous do not think of themselves as being courageous. They have been dealt harsh hands, but they still face each day with optimism and hope.

I feel most courageous when I am: taking the more difficult path instead of the easier, more comfortable route.

Some Things You Might Find Interesting About Me

About “He Keeps On Truckin'”

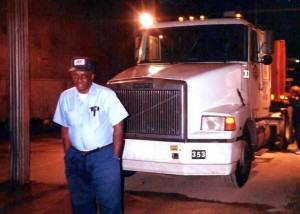

“On the Road.” This answer was given when asked the whereabouts of the long distance truck driver. “He Keeps On Truckin’” tells of the struggles of a father of eight who was “on the road” for over 70 years. It reveals how his truck became his solace and a source of strength and comfort during difficult and turbulent times.

“He Keeps On Truckin'”

The house shook as he coughed. I know he’s not going to work as sick as he is. I lay still under the heavy handmade quilts waiting …and I hear it…the sound of his feet hitting the floor. It’s 2:00 in the morning, it’s pouring rain, his guttural cough continues as he makes his way to the bathroom and the tears pour down my face.

I knew he would return on Friday night, that on Saturday he and my Mom would go to Red and White Grocery and to the laundromat to wash clothes, and on Sunday we would go to church, but I still cried. He is much too sick to go to work, but his thoughts are not on himself. They are on the eight of us sleeping four to a bed and the sooner he gets on the road, the sooner he can pick up his first load and begin his week as a long distance truck driver.

This was my Dad’s routine for all of my life and most of his. He took his first drive in the big rig around the age of fifteen when the owner of a company asked him if he could transport a load for him, not knowing that my Dad didn’t have a driver’s license. He climbed up in the big rig and as an addict experiencing his first high, my Dad was hooked. For over 70 years this was his life.

For many it was a mundane, monotonous life, but for him it was not only the thrill of a lifetime, but insulation from the cruelty that awaited him each day. Closing the heavy steel door offered a sense of security against a segregated society that shunned him because of the color of his skin. As he transported materials thousands of miles weekly, for a moment he was transported from the harsh realities of his world. As he climbed the steps up to his seat, he stepped over the adversities he faced daily, such as standing in freezing rain waiting for cold sandwiches in the back of the restaurant, while other truckers sat warmly at tables eating hot meals. It was in the cabin of his rig that he was reassured of his own worth after being arrested and thrown in jail for driving while black. It was where he was reminded of how blessed he was when he learned of how another African American trucker had been murdered by the KKK in Alabama. There was no, “Yes, Mr. Bossman.” He was the boss of the big rig. For a moment he was in control of his world.

The eighteen-wheeler was not just a vehicle for him. It was his soulmate, his best friend, his mistress. For this was where he pondered over his struggles to provide for a wife and eight children. As much as he loved having the little ones run to meet him weekly, shouting “Da Da,” it provided the solitude he longed for after a weekend with rambunctious children. It was the radio that drowned out the disillusionment of having to leave his wife to manage the home alone, or the disappointment he knew his children would experience as he missed another play, a sports performance, or a graduation.

The big rig was his solace. This was where he regained his strength after seeing the mangled and ravaged victims of the Battle of Iwo Jima. It was where he was reinvigorated each time he was knocked down by injustice and racial discrimination. This was where he planned the building of a home after losing his house in a fire. This was where he cried when one son had multiple operations after nearly losing his eye on the playground and another one was severely burned in a tent fire while camping out with boy scouts. It was the steering wheel that he gripped tightly when he sobbed when his oldest daughter was killed in a car accident, when two of his sons died from cancer, and when his wife of nearly 60 years died from complications from a stroke.

Dad finally retired at the age of 87 and only when he had to have a pacemaker. Recently he celebrated his 90th birthday. He sat in a church full of family and friends but sitting on both sides of him were not his remaining children or his grandchildren. He was surrounded by his trucker brothers, his comrades, his soulmates as they reminisced over the life of a trucker.

When all the accolades and adorations were complete he made his way to the podium. It was another lengthy journey for him. Years of driving has contorted his once six foot frame to the shape of the driver’s seat. Slowly his arthritic, artery-clogged legs made the painful steps with him refusing assistance. He has endured many painful walks. He held the sides of the podium tightly with the same intensity that he once held his steering wheel. As he looked over the crowded sanctuary at the many faces of friends and family who showered him with praises, there was no fear.

He boldly stood before the congregation with courage, confidence and conviction. With a passion that superseded the passion for his truck, he sang praises to his God. He sang without bitterness, anger, or disappointment, but with a heart overflowing with gratitude. And yes, I cried . . . and he keeps on truckin’.

A Few Words about “He Keeps on Truckin'”

Those of us who read “He Keeps on Truckin’” by our second place winner, Vickie Morrow, just fell in love with her father Charlie. What a brave and perseverant man she has portrayed!

We believe there is much to be learned from a man who has faced the challenges that Vickie’s father did over the course of his life—the injustice and discrimination, the haunting memories of war, the loss of his home, several children, and then his beloved wife—without bitterness, blame, or hatred in his heart. We were saddened and angered by some of Vickie’s father’s experiences, and humbled by the dedication he had to his family, his work, and his “trucker brothers.” We got the sense, in reading “He Keeps on Truckin,’” that this is a man who has seen and sacrificed more than most of us ever will. And yet, we read that his heart remains a grateful heart. Our judges found this truly remarkable.

Marcus Tullius Cicero said, “A man of courage is also full of faith.” In Vickie’s moving tribute to her father, Charlie, we encounter a man with a joyful and abiding faith, and a man of deep and inspiring courage.

To learn more about Charlie Blackwell, Sr., please click here to read an award-winning profile feature by Patti O’Keefe of the Caswell Messenger.

Photograph courtesy of The Caswell Messenger.